The Modern Libraries of Orange County, 1951-1991

As new families streamed into Orange County in the 1950s and 60s, they needed more than housing. Our expanding cities added all the other amenities of a livable city, like schools, civic centers — and libraries.

That midcentury boom in library buildings has bestowed on us a remarkable collection of intact Modern libraries throughout the county. They range widely in size, style, and architects, but they all prove how Orange County citizens invested in good architecture for public buildings as a point of civic pride. Their Modern designs express the county’s optimism about a bright, well-educated future for all citizens. Their legacy sets a high standard for public architecture today.

The quality of the architects commissioned demonstrates how seriously city officials took this civic amenity. They range from excellent local firms like Ralph Allen and Knowles and LaBonté, to nationally recognized architects like Richard Neutra, William Pereira, and Michael Graves.

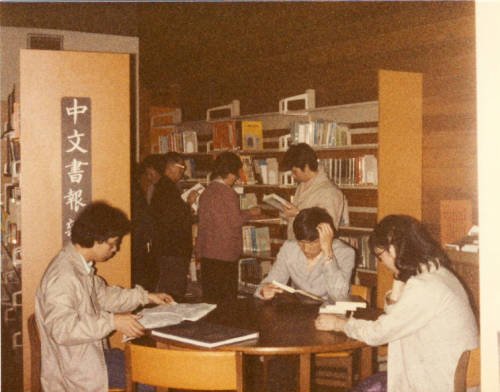

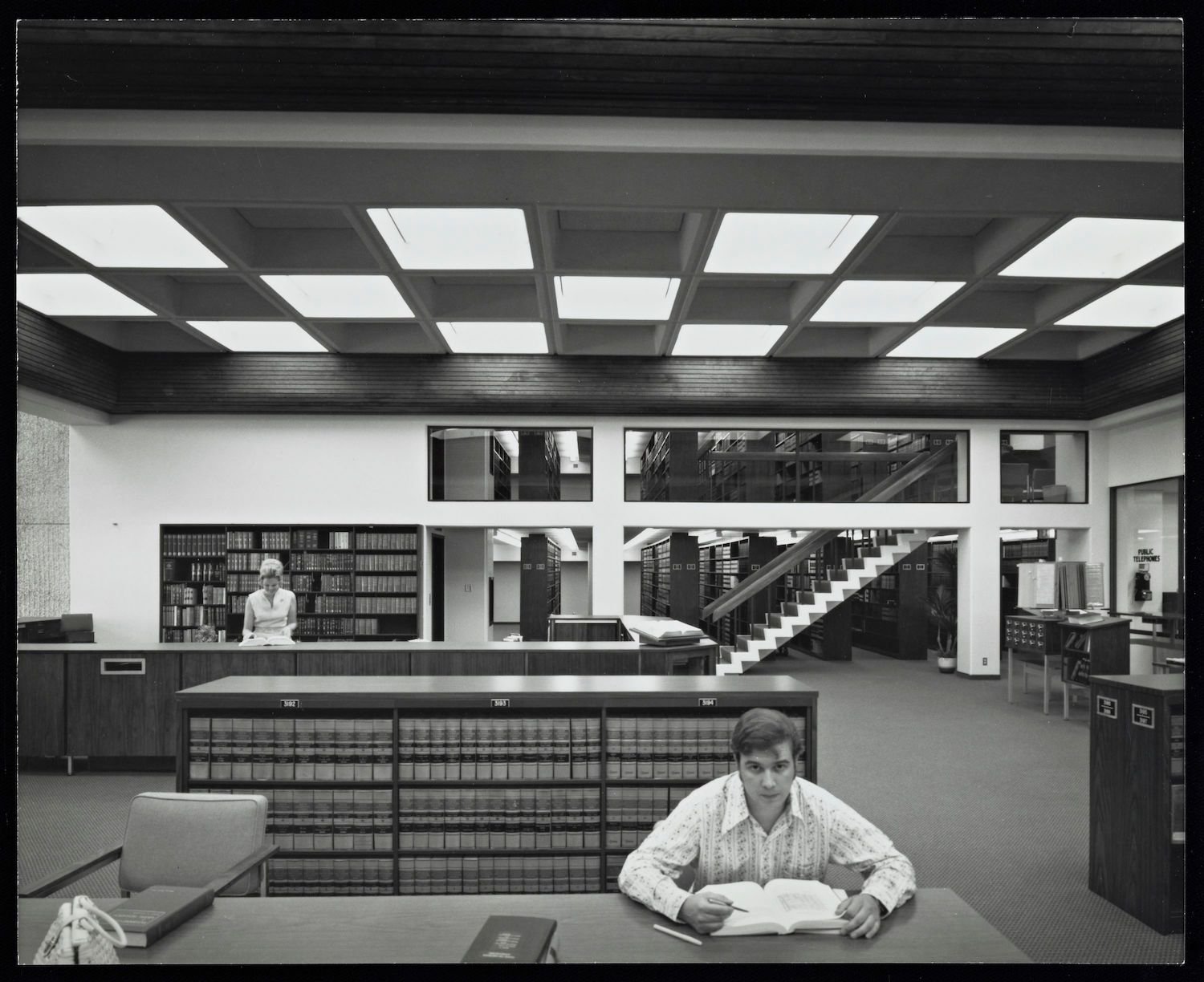

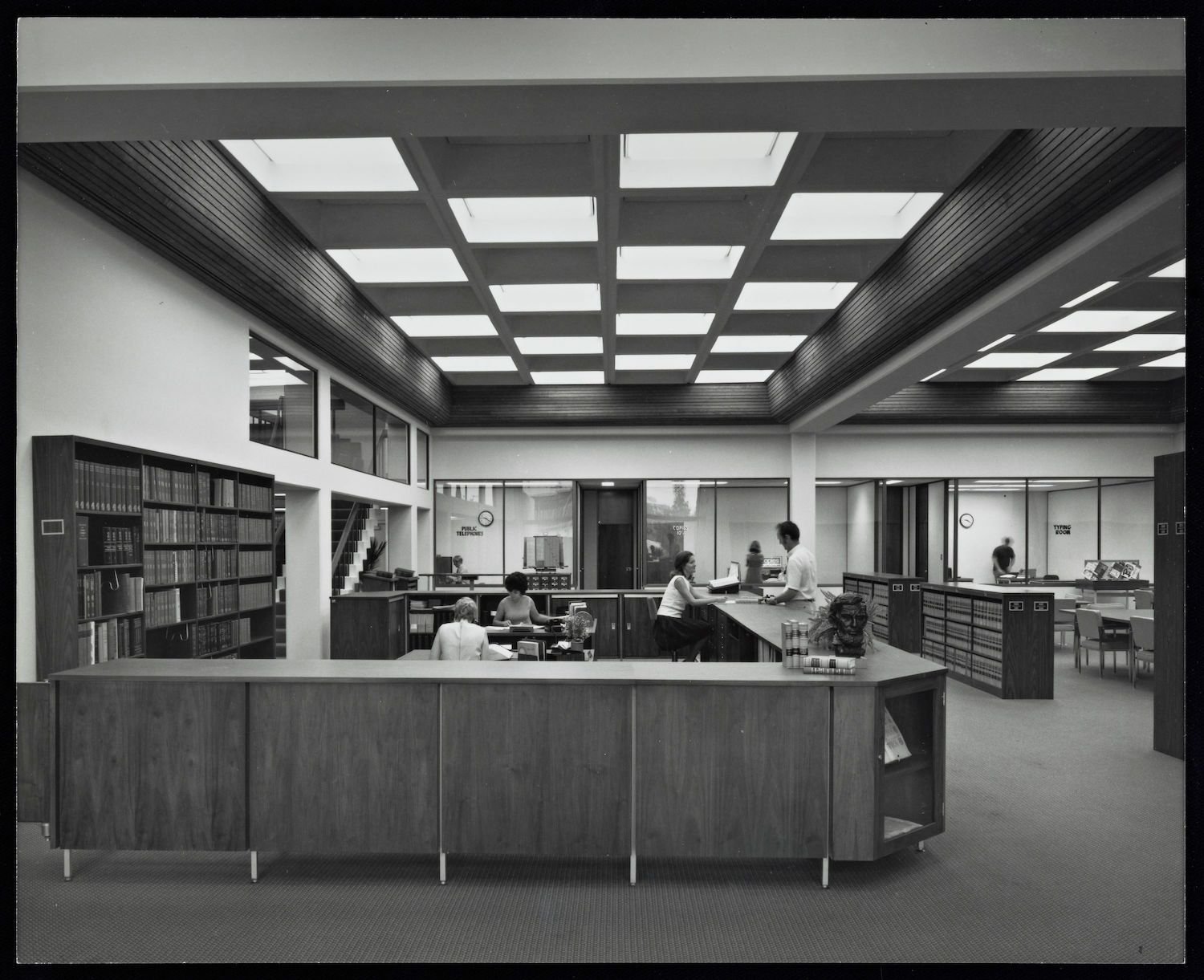

This wide variety of designs served the practical functions of a library. People come to libraries to study, read, browse, relax with a good magazine, or to catch up on the latest news. A library needs plenty of space for the book storage stacks, but the atmosphere of a good library should also be filled with light, with comfortable seating, and be a pleasant place to spend time. That’s where good design becomes essential.

Huntington Beach’s Central library (1975) is an example. Designed by the father and son team of Richard and Dion Neutra, it offers a series of small reading areas, like trays floating on different levels, interspersed with water features that add white noise to mask the distraction of people talking. Each deck offers expansive views of the surrounding park — plus outdoor balconies for a breath of fresh air.

Other libraries also take advantage of California’s beautiful weather by including landscaped walled gardens as outdoor reading rooms, as at Garden Grove’s Tibor Rubin Library (1964) by J.R. Wilde.

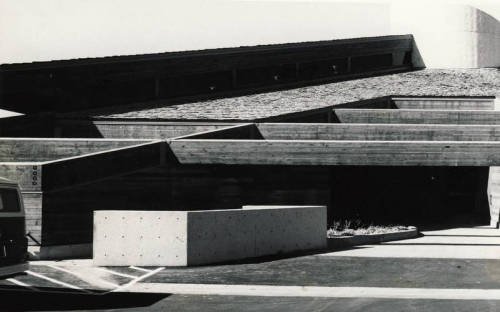

Though smaller than Huntington Beach Central library, Costa Mesa’s Mesa Verde library (1965) makes its reading areas central to its design, by Schwager Desatoff and Henderson, AIA. Outside, visitors see a zig-zagging “folded plate” roof hovering above the main structure. Inside, there’s a surprise. This modernistic cupola is the raised roof that allows for a mezzanine reading area above the stacks and check-out counters. The angular roof creates clerestory windows that let in natural light and tree top views, and its radiating lines create an exciting sculptural focal point overhead.

These examples show the spirit of Modern architecture as it was practiced in Orange County in the mid twentieth century. Their forms follow their functions, as in the appealing reading areas.

Modern materials like concrete and glass are highlighted. The architecture expresses their modern structures. At Tibor Rubin Library the exposed structure of T-shaped beams are part of an integrated beam and roofing system that allows for a broad open floor plan without interior columns.

Besides being functional inside, outside these buildings were meant to be impressive civic monuments. Costa Mesa’s Mesa Verde library is a classic modern example. Two symmetrical buff brick walls flank the glassy entry inviting you inside. The zig-zag roof gives the building distinction, like the dome on a traditional city hall or the steeple on a church.

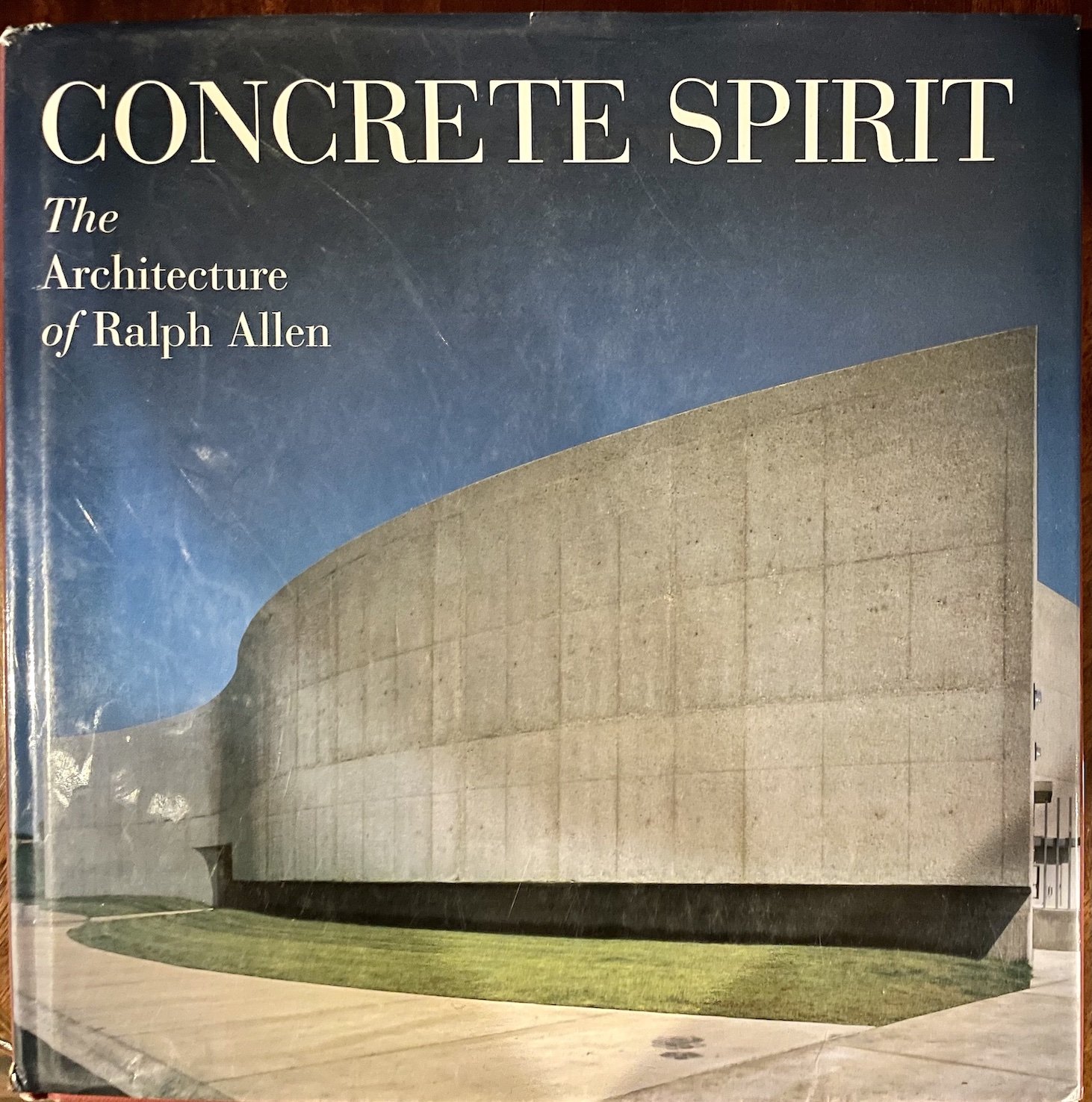

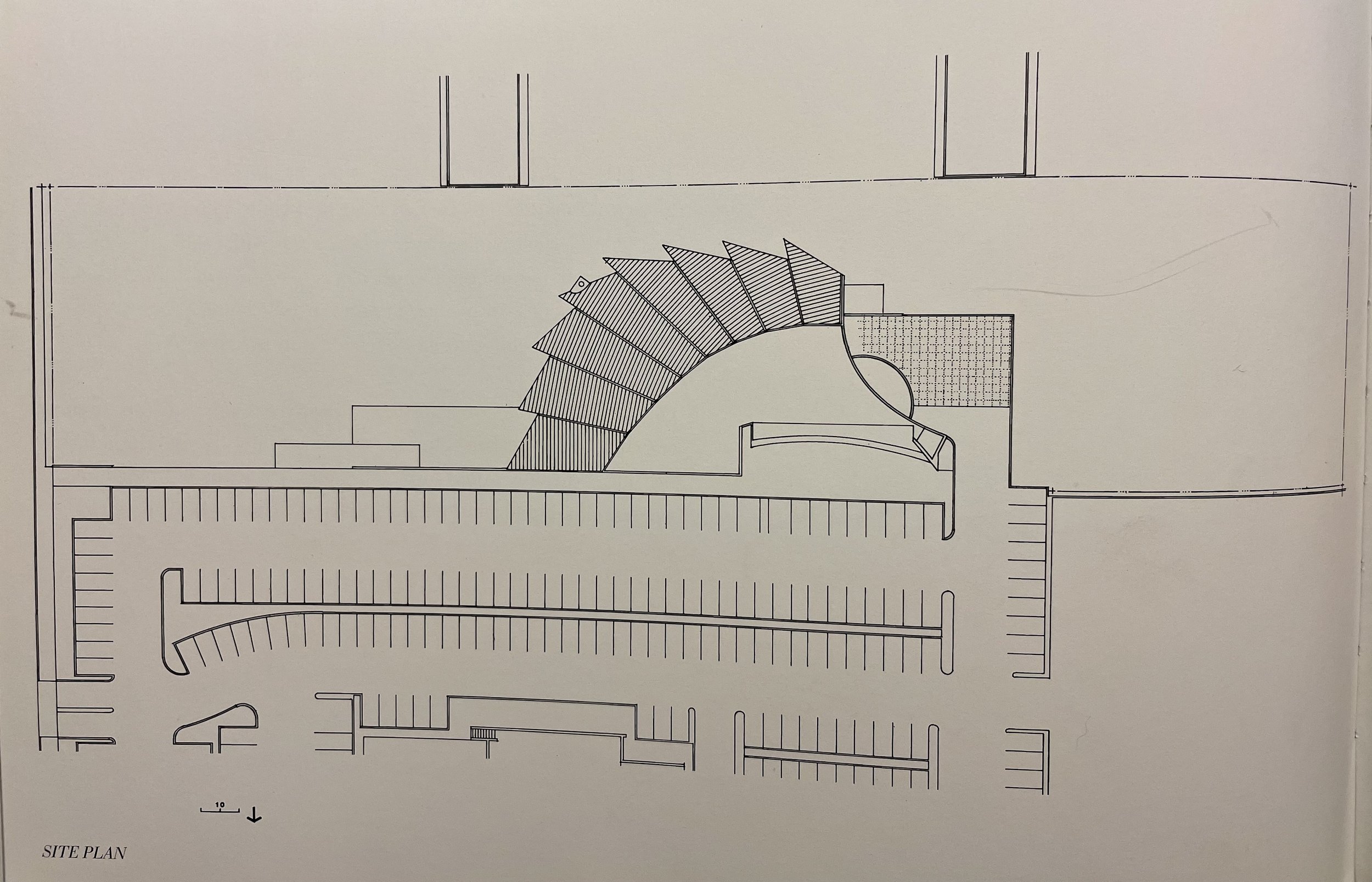

The range of imaginative designs in these libraries would make them worth a trip even if you’re not checking out books. Architect Ralph Allen’s Fountain Valley library (1991) is one of the most extraordinary. Its curving concrete walls are pure sculpture, and reflect the shapely Brutalist designs of the important modern master architect Le Corbusier. Compare Allen’s sweeping entryway to Le Corbusier’s famous chapel at Ronchamp, France. It’s like a frozen wave.

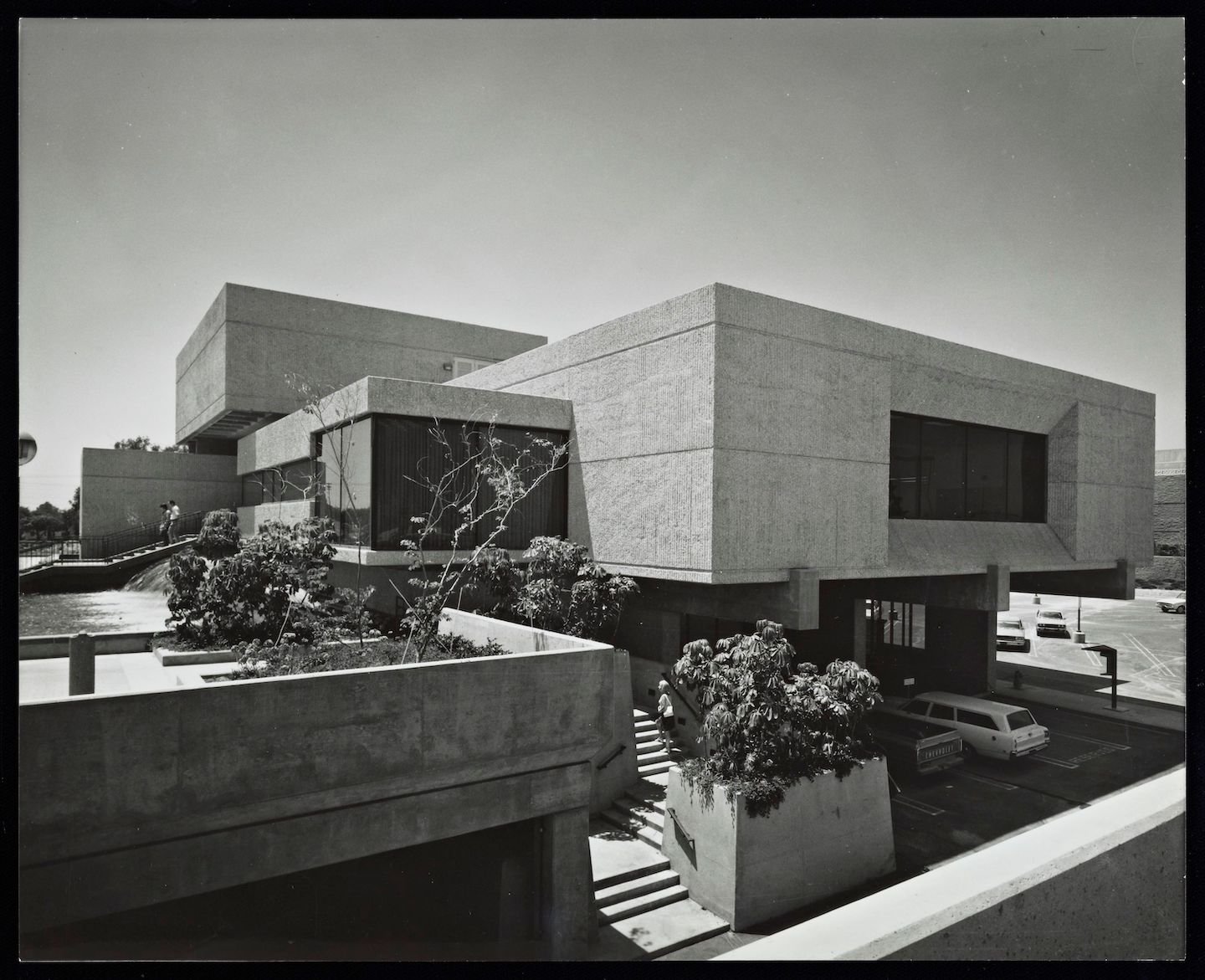

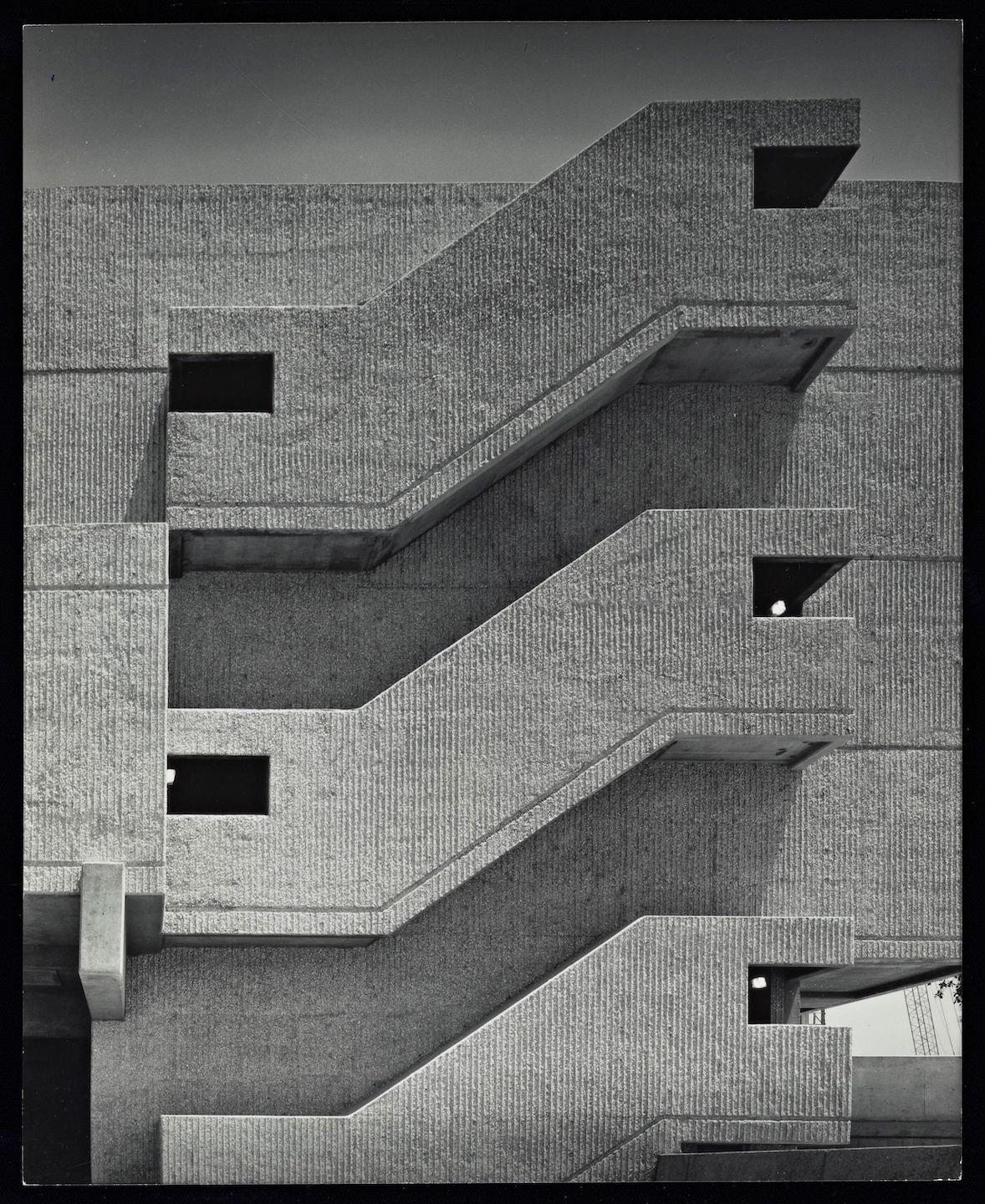

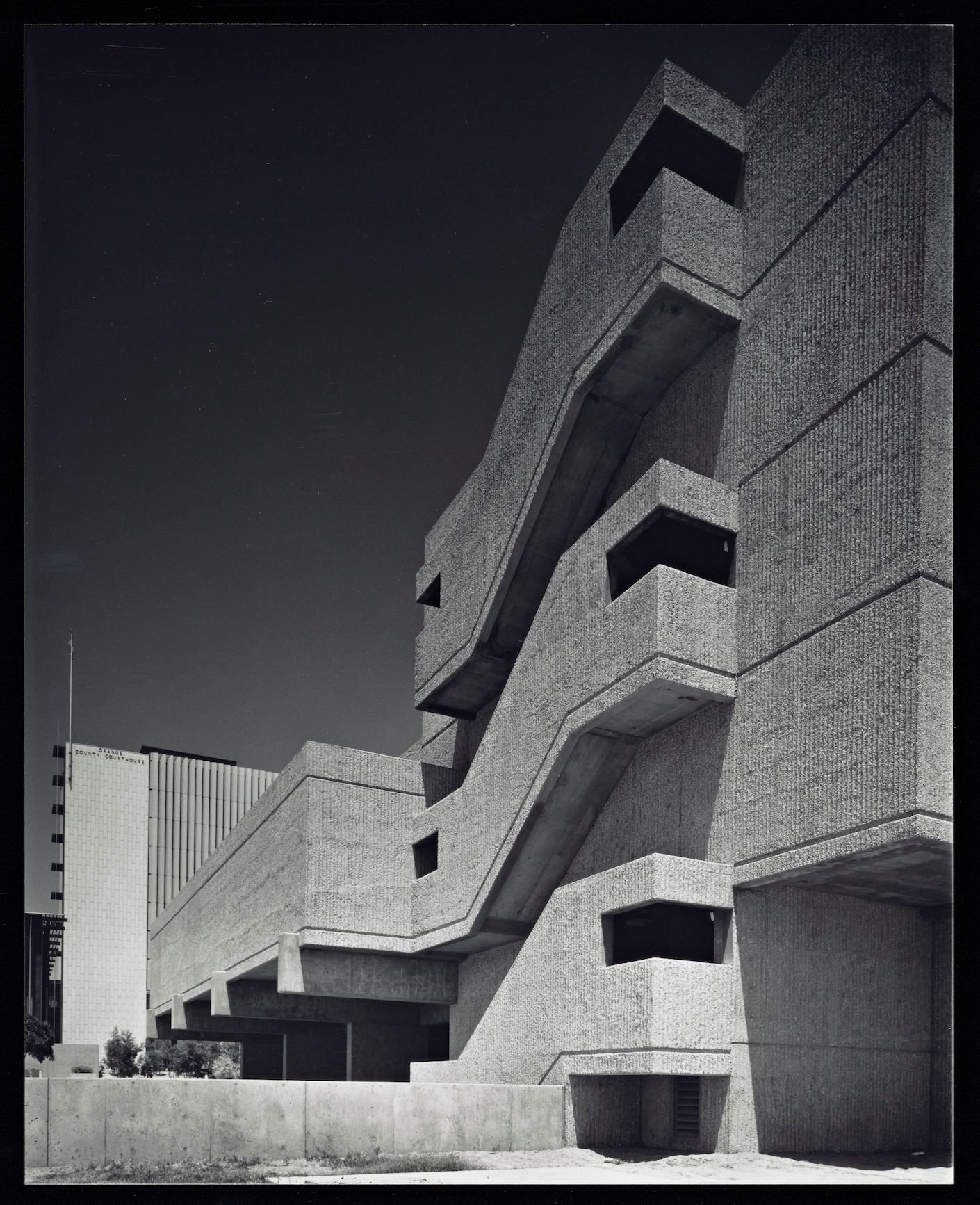

Ralph Allen’s other Brutalist library, for the law library in Santa Ana, takes a very different direction. It is a carefully crafted composition of concrete boxes, each a different size, each hovering over or next to the next. Diagonal stairways protruding from the face of the building, one stacked on top of the other, create their own sculptural moment while serving a practical purpose. At this library, Allen uses a roughly textured concrete finish that captures sunlight and shadow, rather than the smooth surface of the Fountain Valley library.

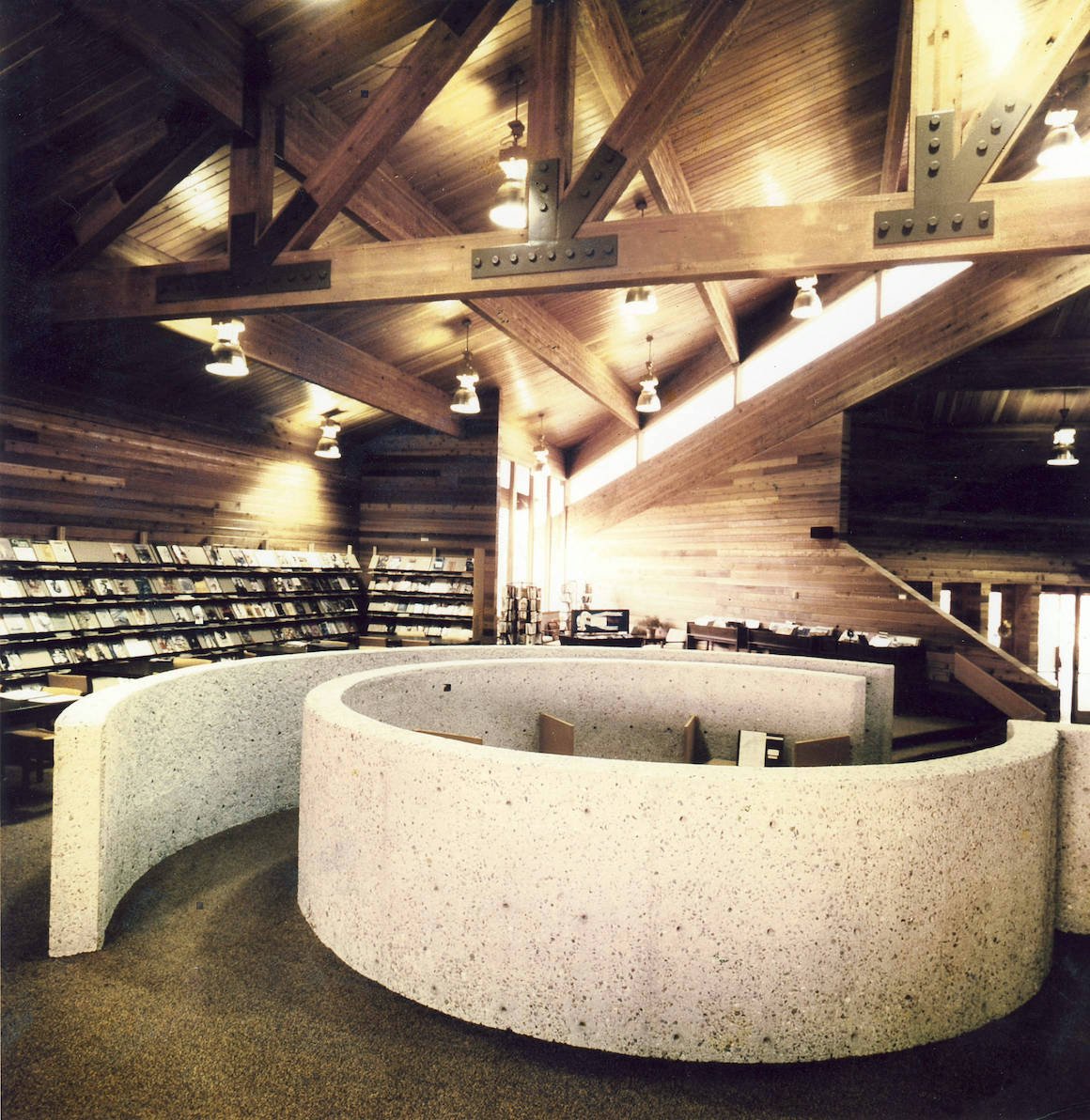

For pure drama, Irvine’s University Park library (1975) by Knowles and LaBonté may win the prize. It has a spiral plan around a large turret-like concrete cylinder at its center. This serves as a tent pole, allowing the roof planes to drape down from it, one lower than another, allowing natural light from clerestory windows at each step.

Inside the drama continues with a forest of heavy timber trusses that support those high roof planes. Inside a spiral ramp echoing the roof form lead from the entry level to the main floor, though it was removed in a 2010 remodel.

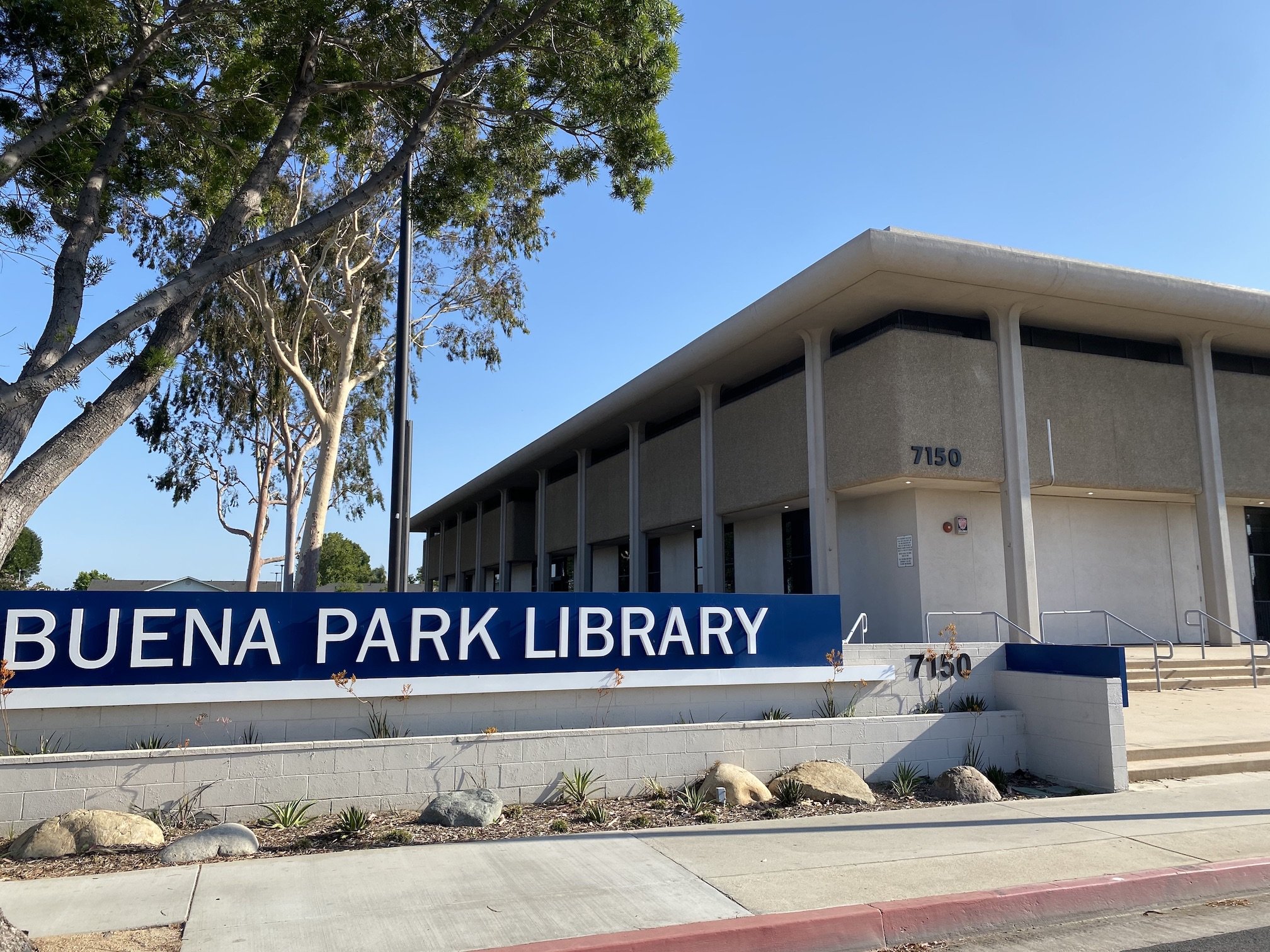

The range of distinctive Modern designs is seen countywide. Huntington Beach’s Main Street library (McClellan, MacDonald & Markwith, 1951), one of the first after World War II, was already looking to a modern future with its slanted pilasters and two story window in the Late Moderne style. La Habra’s early library takes on the low-slung style of the Ranch houses appearing in suburban tracts at the time, Buena Park library (1969) with its sculpted columns was designed by William Pereira, UC Irvine’s master planner and architect of several UCI buildings, including its Langson Library, designed with architects Jones and Emmons. The Cypress Library (Ralph Allen, 1976) and Garden Grove Main branch (Wilde, Wilcox, & Yeo, 1969) reflect yet another modern theme, the library as a pavilion, with a deep roofline and a wide facia, all held aloft on columns. More recently, the Katie Wheeler library in Irvine reconstructed the original Irvine family ranch home on the site.

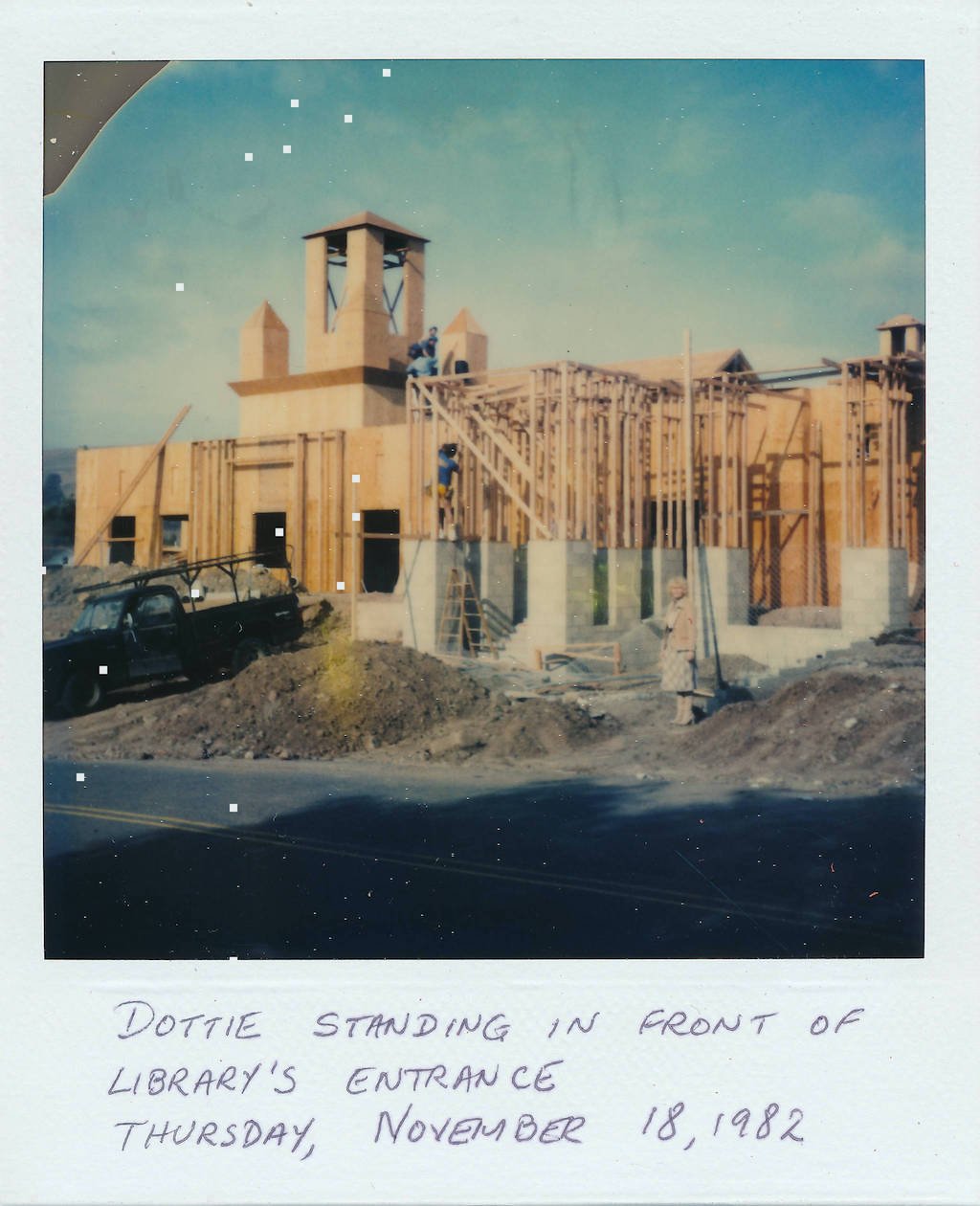

Orange County maintained this high standard for civic design into the 1980s, even when architecture moved from Modernism to Postmodernism. The best example is the San Juan Capistrano library (1982-1983) by nationally renowned architect Michael Graves, one of his best known works in the Postmodern style. Its cupolas, thick stucco walls, and courtyards echo the historic architecture next door at Mission San Juan Capistrano; Postmodern design intentionally reflects the history and culture of its location. But where the earlier Modern libraries had large open floor plans, Graves went in a very different direction. He divided the library up into a multitude of distinct rooms, large and small. But his intention was the same as in the modern plans: to create a variety of spaces for people to enjoy, for both large gatherings and quiet individual reading and study.

These libraries serve children, families, students, businesspeople, citizens — everyone — with good Modern design as they go about their daily lives. Our libraries are an excellent example of Orange County’s rich architectural heritage.

By Alan Hess, Architect, Historian, and Chair, Preserve Orange County