Taking Stock: The City of Tustin’s Preservation Initiative

By Jason Foo

When people think of Orange County cities with notable collections of historic buildings, Santa Ana, with its late 19th and early 20th century commercial core and the late modern civic center buildings, or Orange, with the small-town charm of the National Register-listed Old Towne, probably come to mind.

Tustin, with its more suburban landscape may not merit the same consideration, at least not initially. But take a detour down one of its many tree-lined streets, where you are certain to spot one of the city’s significant number of well-preserved Victorian and Italianate residences, or drive through one of its first housing tracts designed by Cliff May Homes and you should begin to understand the pride that locals have in its historic built environment.

An Early Adopter

The Mary Tustin-Lindsay House dates back to the city’s settlement period and is thought to be one of the few intact board-and-batten houses remaining in Orange County from the era. The home of Mary Tustin, it was moved to its present location in the 1880s after her husband, Columbus Tustin, died in 1883. It remained in the Tustin family until 1943. The property, which includes the adjacent 1910 Patton residence, is for sale. A development proposal calls for the reuse of the houses as a dining venue, with an outdoor seating area between them.

Some contend that Tustin stands out among Southern California cities of its size due to its number of intact historic resources, including pioneer buildings from its founding period in the 1880s. In recognition of this, the City of Tustin has taken more steps than many of its county neighbors to ensure the preservation of its resources.

The City is in the midst of its third comprehensive survey since 1990. With aging 1960s- and 1970s-era buildings gaining in significance, the survey will be the first to include the post-war period through 1976, a time of major growth for the city. Architectural Resources Group is the consultant for the project which is expected to be completed on schedule later this year even with the challenges of pandemic-related stay-at-home orders.

Tustin is one of an estimated 11 cities in the county to have conducted a citywide survey to document its historic and cultural resources. It is one of eleven municipalities to have Mills Act programs and one of three to be recognized as a Certified Local Government (CLG) by the National Parks Service and the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). A citywide survey is one of several requirements a local community must meet in order to become a CLG, a designation that makes it eligible for state and federal grants to fund preservation projects. Tustin was the first city in the county to gain CLG status in 1991, followed by San Clemente in 1993 and Santa Ana in 2002.

Making History

The City of Tustin’s 2003 survey update used 45 years as the age threshold for identifying resources. The survey added 150 properties to the previous survey from 1988-1990.

Tustin’s preservation program began in the late 1980s when several developments in Old Town were proposed, including higher density housing, that residents felt were incompatible with the area’s character and single-family zoning. In 1987, in response to these concerns the city imposed a moratorium on land use changes in the Old Town area which led to the adoption of a preservation ordinance a year later focused on maintaining the fabric of the downtown core.

The city established the Historic Resources Committee (then called the Cultural Resources Advisory Committee) to advise the city council and planning commission in development decisions and the Cultural Resources District (CRD) to encompass Old Town. Bounded by the Santa Ana (I-5) Freeway to the south, First Street to the north, the Costa Mesa (SR-55) Freeway to the west, and Prospect Avenue to the east, much of the district is contiguous with the original boundaries of the city. It was designated as an overlay zoning district, adding to its existing land use requirements, to recognize the importance of Old Town.

The first survey, which began in 1988 and was completed in 1990, identified 270 pre-1940 resources. The inventory included buildings with a variety of uses, among them automotive service, blacksmith, lumberyard, and military. Architectural styles range from early commercial buildings with Western-style false fronts to Period Revival residences. To evaluate a property’s significance, surveyors used SHPO-based standards, with results interpreted into a final A through D rating system. This system was of particular use for residents to determine if their properties were eligible for the Mills Act, a statewide program that enables participating local governments to offer residents tax benefits for maintaining their historic properties.

The 2003 survey updated the inventory and added 150 additional properties, including resources that had reached 45 years old between 1990 and 2000. It used the criteria set by the California Register and the National Register, replacing the grading system with the more comprehensive California state status codes. The current survey is employing the same practice and, in addition, producing for the first time a digital database capable of being integrated with GIS mapping.

The Purpose of Surveys

The Tustin Historic Register Plaque Designation Program includes the first doctor’s office in Tustin at 434 El Camino Real (1885). At this time, there are 63 properties on the register that are designated with a plaque. For some commercial buildings, descriptive text such as “First Doctor’s Office in Tustin,” helps to identify the most prominent business at the location.

An historic inventory can be useful to municipalities in many ways. It can unlock funding and benefits to cities and its residents. It fosters civic pride and local identity. In Tustin, if a property is included on the inventory it is eligible to be nominated for the city’s historic register, also known as the plaque designation program, for consideration by the planning commission. There are 63 resources that display plaques, from ornate to nondescript commercial buildings, grand Victorians to modest board-and-batten houses.

A survey should also inform future development and planning in cities. The first two Tustin surveys led to the adoption of residential and commercial guidelines for the Cultural Resources District based on the evaluation of historic features, and informed owners of the contributing elements of their properties and when a certificate of appropriateness was required for changes.

The listing of a property on the inventory does not confer formal historic designation nor does it provide protection from alteration or demolition. In Tustin, the best safeguard for an historic resource is its inclusion in a cultural district or, if it exists outside of one, its recognition as a Designated Cultural Resources by city council. This makes proposed changes subject to design review. It is noteworthy, then, that the current survey intends to recommend that the boundaries of the CRD be expanded to include the neighborhoods north of First Street, with its number of small bungalows and Lockwood Terrace’s 1950s-era tract housing. And with properties from as recent as the mid-1970s becoming eligible for inclusion, more resources outside of Old Town will be added and new cultural resources districts may be considered.

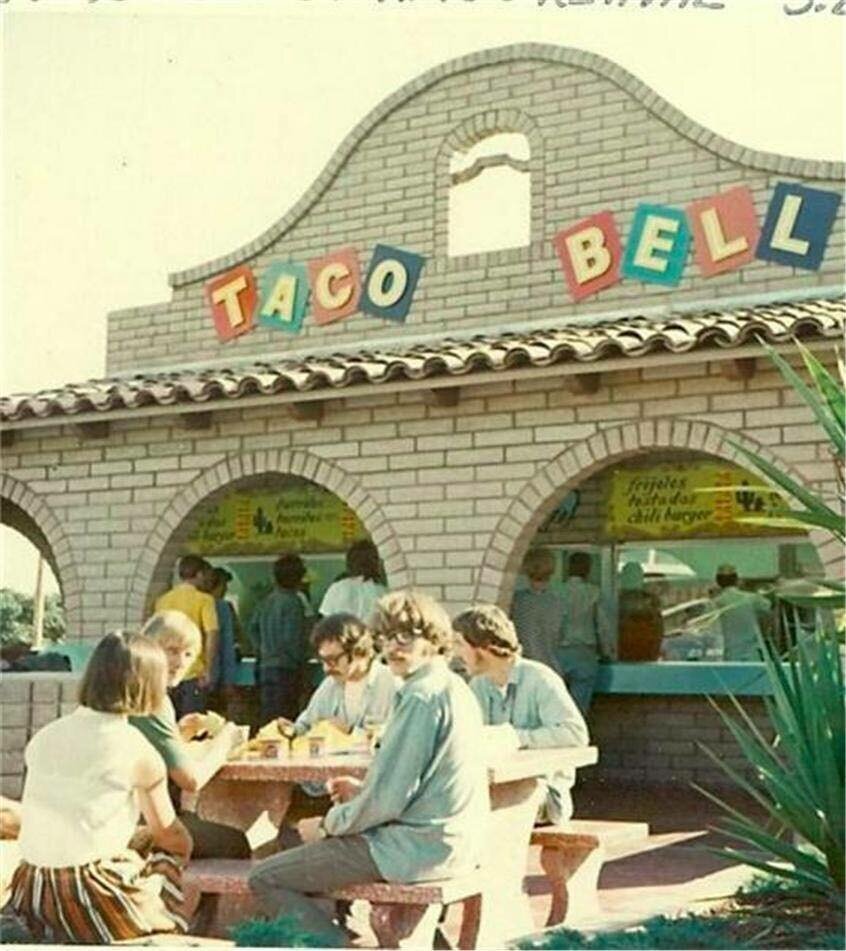

The building form (above) is immediately recognizable. The old Taco Bell at 14232 Newport Avenue is unoccupied but it is one of the first Taco Bell taco stands, and one of only a few remaining in the Mission style first introduced by Glen Bell in 1962. With this year’s survey considering properties with date of construction up to and including 1976, this original Taco Bell store could be added as a resource.

“Sensible” Preservation

Surveys also help guide communities in maintaining sensible preservation goals. The identification of non-contributing buildings and historic buildings that have been altered and are unlikely to be restored allows a city to prioritize certain historic resources overs others. It is not surprising, then, that Tustin and preservationists have been at odds over what is considered sensible. While the city’s preservation program was launched in response to public outcry over proposed development, some local preservationists have complained of a more opaque process governing recent decisions at city hall.

In 2007, the advisory Historic Resources Committee that was established at the same time as the CRD was dissolved by the city council and its responsibilities were reassigned to the planning commission. The reason given was “to streamline city committees and processes.” The commission was allowed to act in place of the HRC in its new role as the Historic and Cultural Resources Advisor. This fulfilled the CLG requirement for a preservation committee even as the city council pondered if it wanted to maintain its status. There were unsuccessful attempts to reinstate the HRC in 2012 and 2018.

Locals point to the Vintage at Old Town development as an example of when development and preservation interests diverge. In 2016, tenants in the 1960s-era industrial park that borders the CRD were given 30-day notices to vacate after the city rezoned the land from industrial to planned community. Residents mobilized against the proposed high-density development. A group called Citizens for Tustin’s History filed a petition against the developer and the city alleging that they violated the California Environmental Quality Act when it determined that an environmental impact report was not required. The case was settled out of court, but the property was razed for a 140-townhouse community with stylized historic façades.

The city courted controversy when it approved the demolition of a 1960s-era industrial park, featuring Japanese-style roofs with blue clay tiles over the entrances of the buildings, for a high-density townhouse complex called “Vintage Old Town” on the edge of the Cultural Resources District.

Decision-making pertaining to historic districts or potential resources often benefits from a slowed-down process in which different interests help shape the outcome. Fast-moving development is one reason why having a regularly updated inventory of resources is crucial for preservationists. As Mark Wilcken of the Tustin Preservation Conservancy states, “What’s important about this survey is that nothing is being left behind, especially things that are from the 50s and 60s era.”

Then and Now. The former Charles O. Artz General Merchandise Store (1914) is now the restaurant, Rutabegorz, 1950 & 1958 W Main Street. In 1988, the Tustin city council approved an ordinance that created the Cultural Resources District. Commercial and residential design guidelines are used to preserve the historic fabric of Old Town Tustin.

Jason Foo

In addition to his work for Preserve Orange County, Jason Foo is a longtime volunteer for the Los Angeles Conservancy. He has written articles on architects J. Herbert Brownell and Ron Yeo for Tracts. Jason lives in Huntington Beach.