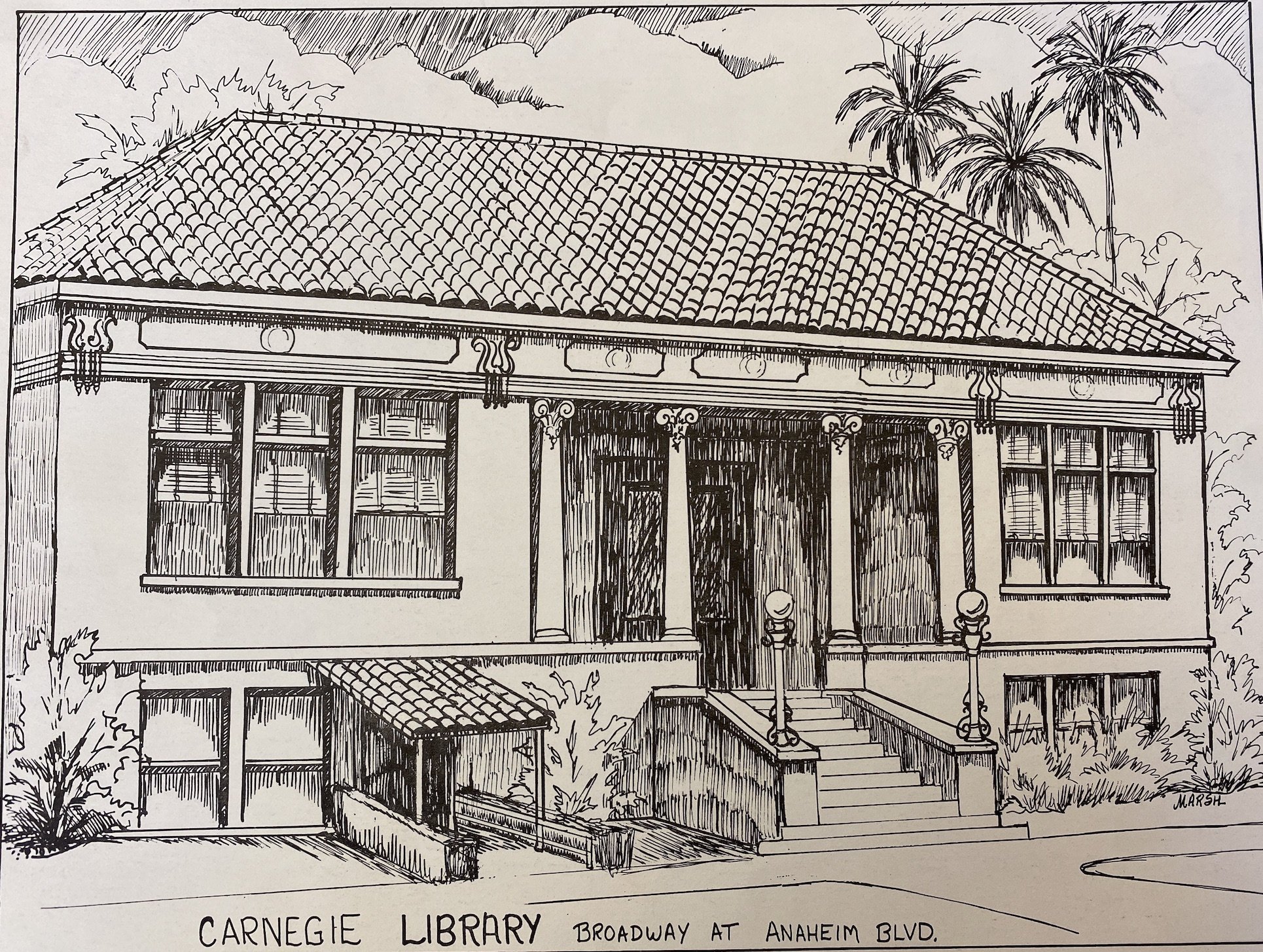

Anaheim Carnegie Library

241 S. Anaheim Boulevard, Anaheim, CA

John C. Austin, FAIA (1908)

Historic buildings that have been adapted for a second life as cultural centers have had a successful track record in Orange County. The Muckhentaler Center in Fullerton and Casa Romantica Cultural Center and Gardens in San Clemente were originally designed as residences in the 1920s. What are today well-loved community institutions were probably at one time contested sites that preservation-minded residents spent years to protect and achieve their vision. This was the case in Anaheim with Muzeo Museum and Cultural Center. Muzeo’s building—the former Anaheim Public Library-- was already a beloved public resource but it took years of advocacy to generate funds and defend it against the 1970s urban renewal ethos that motivated the City of Anaheim at the time.

“Library to be Handsome:” A Brief History of the Anaheim Carnegie Library[1]

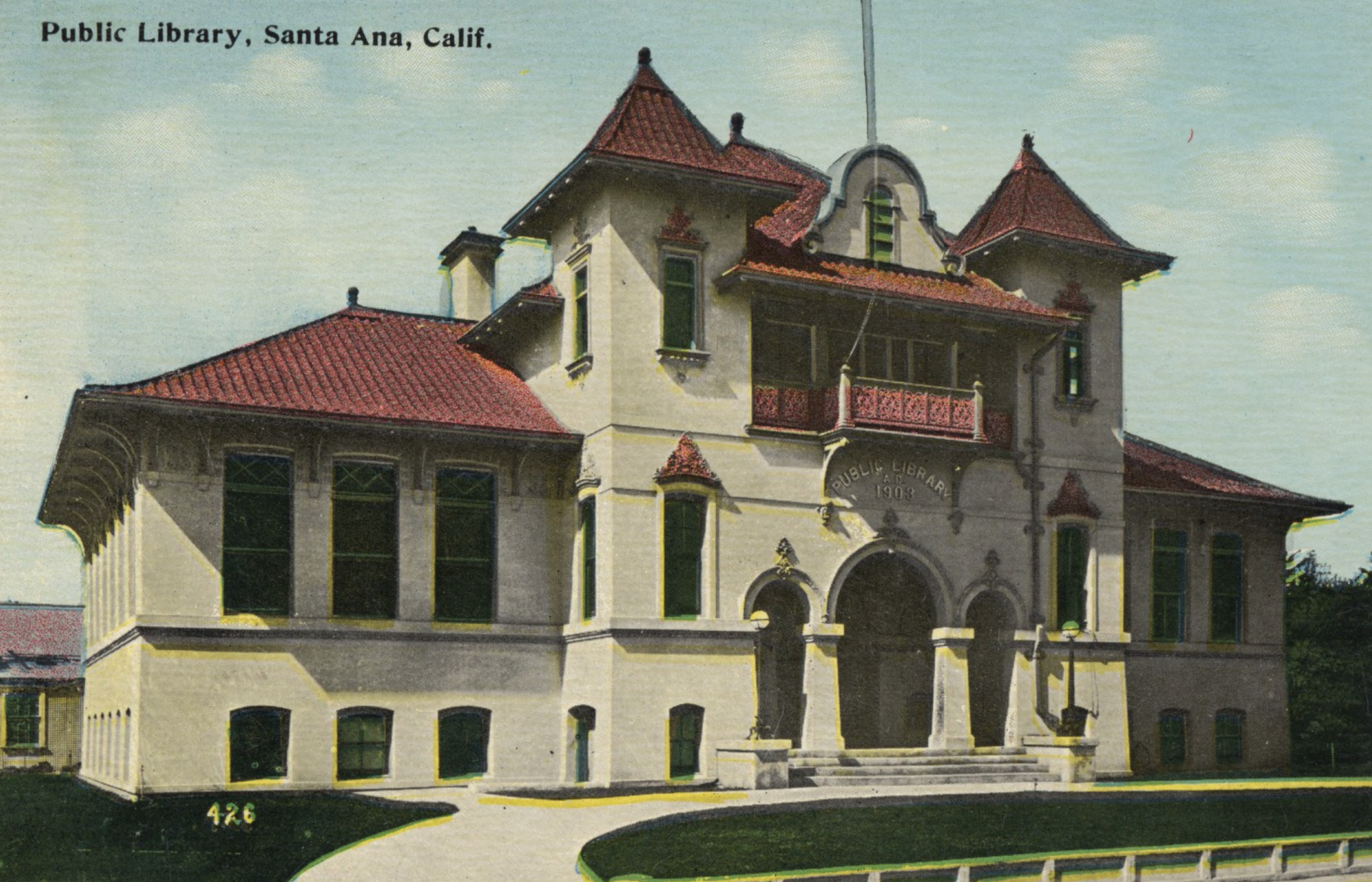

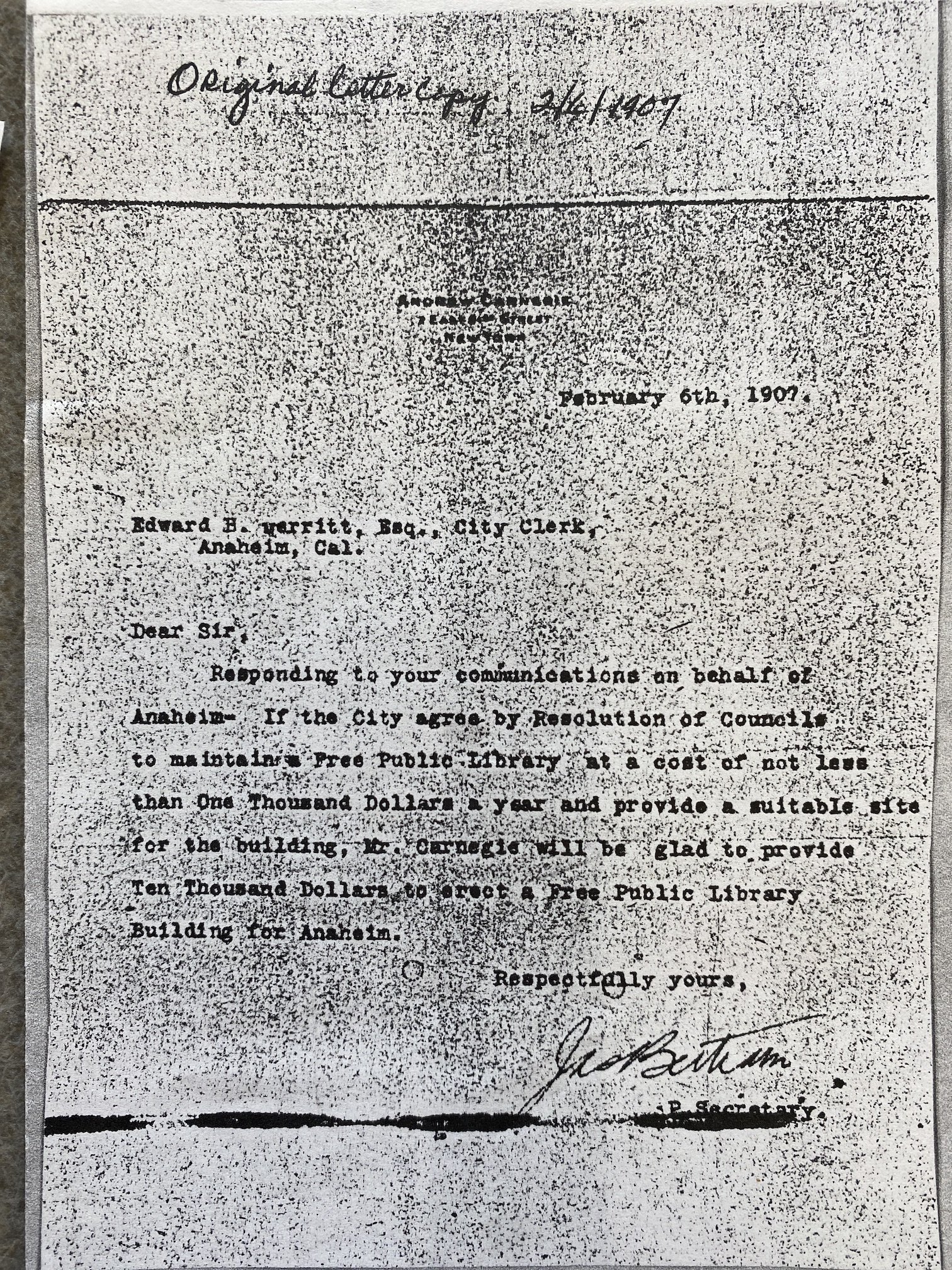

In the early 1900s a small group of residents with support from the local Chamber of Commerce began the process of establishing a dedicated library building in Anaheim. The industrialist, Andrew Carnegie, had been providing grants to cities to build free public libraries since 1889, and the Orange County cities of Santa Ana and Fullerton had received grants in 1902 and 1905 respectively. By 1907, Anaheim had met the two funding conditions set by Carnegie.[2] First, the land was secured with clear title. Thanks to donations made by 75 residents, the City was able to purchase the corner lot owned by Adelaide and William Konig at the present site, the northwest corner of Los Angeles Street (now Anaheim Boulevard) and Broadway.[3]The second condition was met when the Anaheim trustees formally committed to spend 10% of the building cost per year in perpetuity to maintain the building.[4]

Though the Carnegie foundation reviewed and commented on plans, they did not dictate architectural style.[5] The Classical Revival style that was employed in the Anaheim library was the choice of the architect, John C. Austin. The style was by no means outside the norm for either Carnegie libraries or architecture of the era. Over 60% of libraries constructed in California of Carnegie money were a version of the Classical Revival style.[6] The Carnegie libraries in Huntington Beach (1913) and Orange (1908) were both in the style. But only a fraction incorporated elements of the Mission or Spanish traditions. Anaheim’s hipped roof made with red clay tile material was a nod to regional history.

John Austin’s plans for the library were chosen in a competition overseen by the library trustees in which six firms participated.[7] Austin (1870-1963) was an auspicious choice. He would go on to become one of the most prominent architects in Southern California, practicing in Los Angeles for over 50 years and named a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1913. Before the Anaheim library, Austin had designed a couple of hotels and churches, and some large scale residences. In the 1920s and 1930s, Austin was directly associated with major projects in Los Angeles such as Shrine Auditorium, Los Angeles City Hall, and the Griffith Park Observatory.[8]

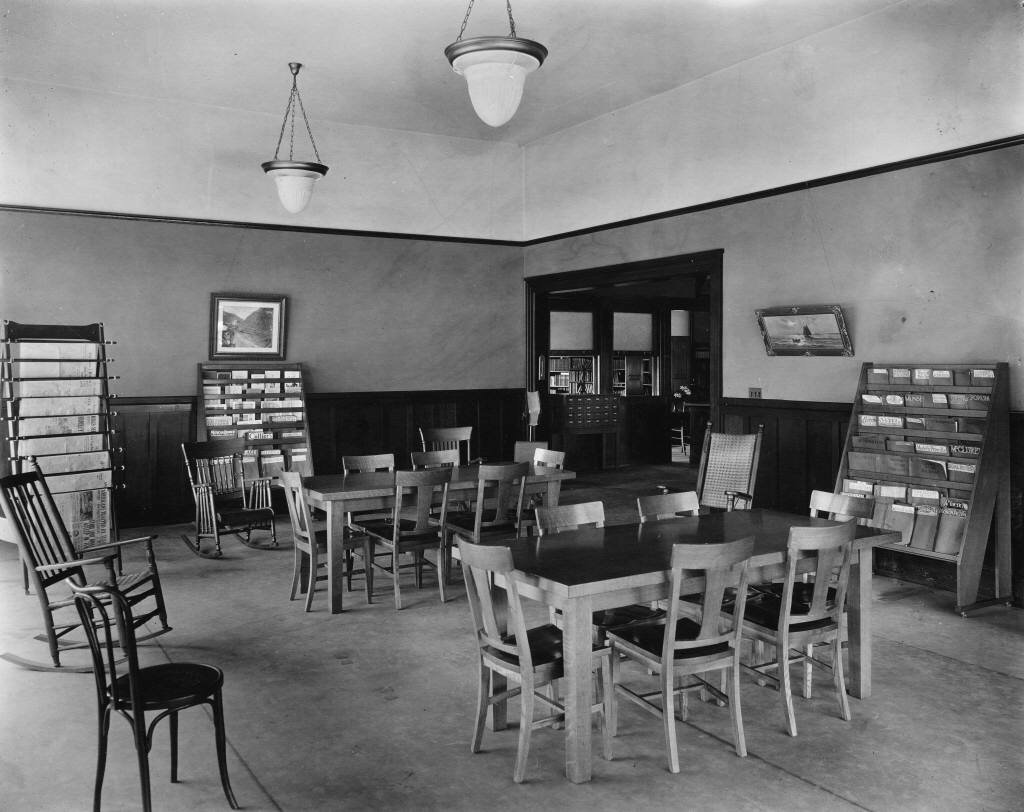

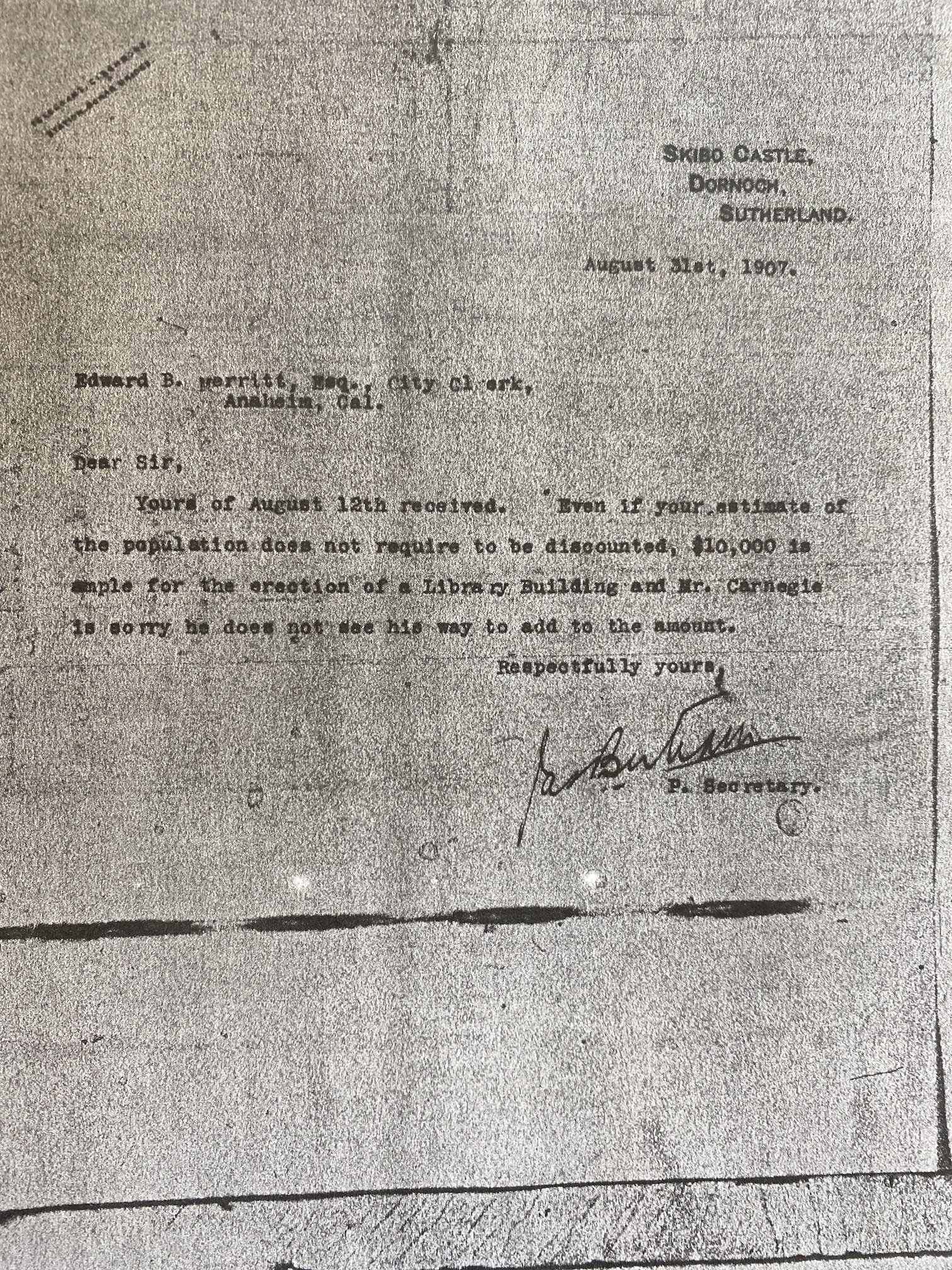

An initial request of $15,000 was politely but firmly rejected by Carnegie and the amount of $10,000.00 was ultimately donated to Anaheim based on the city’s size.[9] Construction of the building by Kuechel & Rowley of Orange (Chapman College) was completed within budget and the new library was dedicated in November 1908.[10] It took the library board a few years to fund books and furniture to fill the new space but in 1928 there were over 12,300 volumes, and by 1953 the 35,000 volumes far surpassed the 25,000 book capacity of the building.[11] The library was a beloved building and a point of pride for the city. Librarians of remarkably long tenure provided dedicated service to generations of Anaheim residents. Elizabeth Calnon, who was hired in 1915, retired as head librarian in 1953; and Elva Haskett was the children’s librarian from 1925 to 1962.[12]

From Library to Museum

When the Carnegie library opened in 1908, Anaheim had a population of 1700 people. Two branch libraries were opened in subsequent years to accommodate neighborhoods beyond the core and by the 1950s, city officials were considering building a new main branch. Just a couple of blocks from the Carnegie, a new library was built in 1963 and dedicated in 1964 on Broadway at Harbor Boulevard. The Carnegie library was closed in 1963 and only intermittently used until City Hall had outgrown its building and needed space for some of its own staff. The City’s personnel department was installed in the library in 1966.

Orange County grew exponentially in the post-World War II period, and Anaheim was becoming one of its biggest cities. Disneyland was an obvious driver of tourism jobs but manufacturing too was attracting more and more residents. The City’s keystone planning effort to accommodate this growth involved densifying what was by the 1970s a historic downtown. “Project Alpha,” was the far-reaching redevelopment plan adopted by City Council in 1973 which foresaw the demolition of the historic downtown, including the old library.[13]

Several historic buildings were eventually demolished in downtown Anaheim but the library seemed to have enough public support at critical junctures. The first most consequential action occurred in 1974 when the Cultural Arts Commission led by Earl E. Dahl convinced the City Council to consider a lease arrangement with a third party organization to ensure the restoration and reuse of the public building.[14] At that time, City Council agreed the library shouldn’t be demolished but did not commit to a solution. However, residents were encouraged and soon established the Anaheim Community Steering Committee for a Historical Museum.

Also in this period, a parallel group called the Anaheim Society of Preservation Action undertook the nomination of twenty-four buildings to the National Register of Historic Places- eleven of which, including the library, were in the city’s redevelopment zone. At the time, formal objections to the nominations made by property owners and the City kept the nominations from going forward. But in February 1978, City Council adopted a resolution committing to restoring the Carnegie library and converting it to a “historical library, research center, and museum.”[15] Following this resolution, funds from the Anaheim Redevelopment Agency and the City were allocated to commission engineering and architecture plans for the library’s restoration.[16] And when the National Register nomination for the library was submitted by Diann Marsh and Andrew Deneau, two of the founders of the Anaheim Historical Society in 1976, the City did not object and the building was listed on the National Register in 1979.

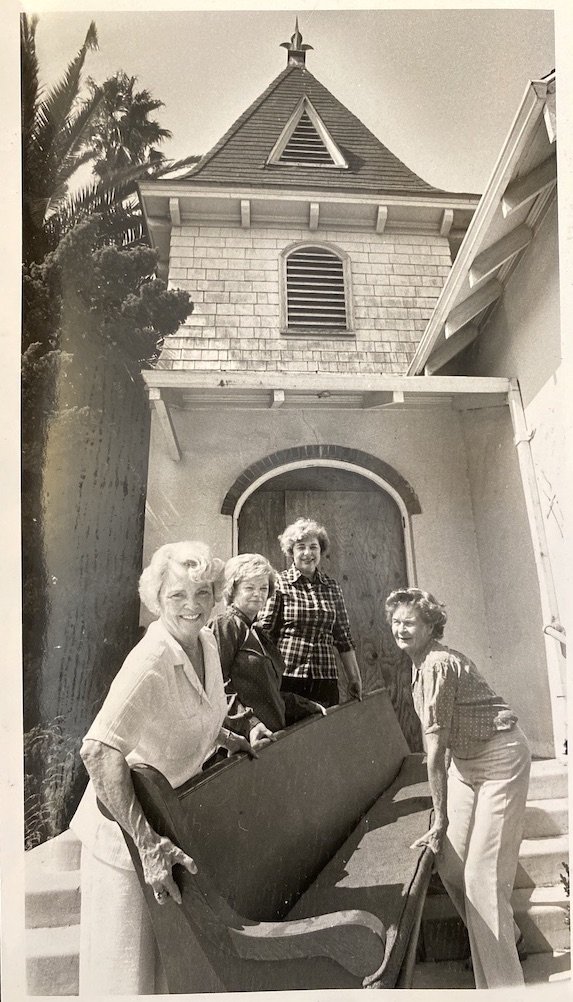

By September 1980, the City was allowing the Anaheim Community Steering Committee to collect and store artifacts from Anaheim’s earliest days inside the building.[17] Soon after, members of the steering committee formed the non-profit Anaheim Museum Inc. with the purpose of securing a lease, fundraising, and getting a new local history museum off the ground.

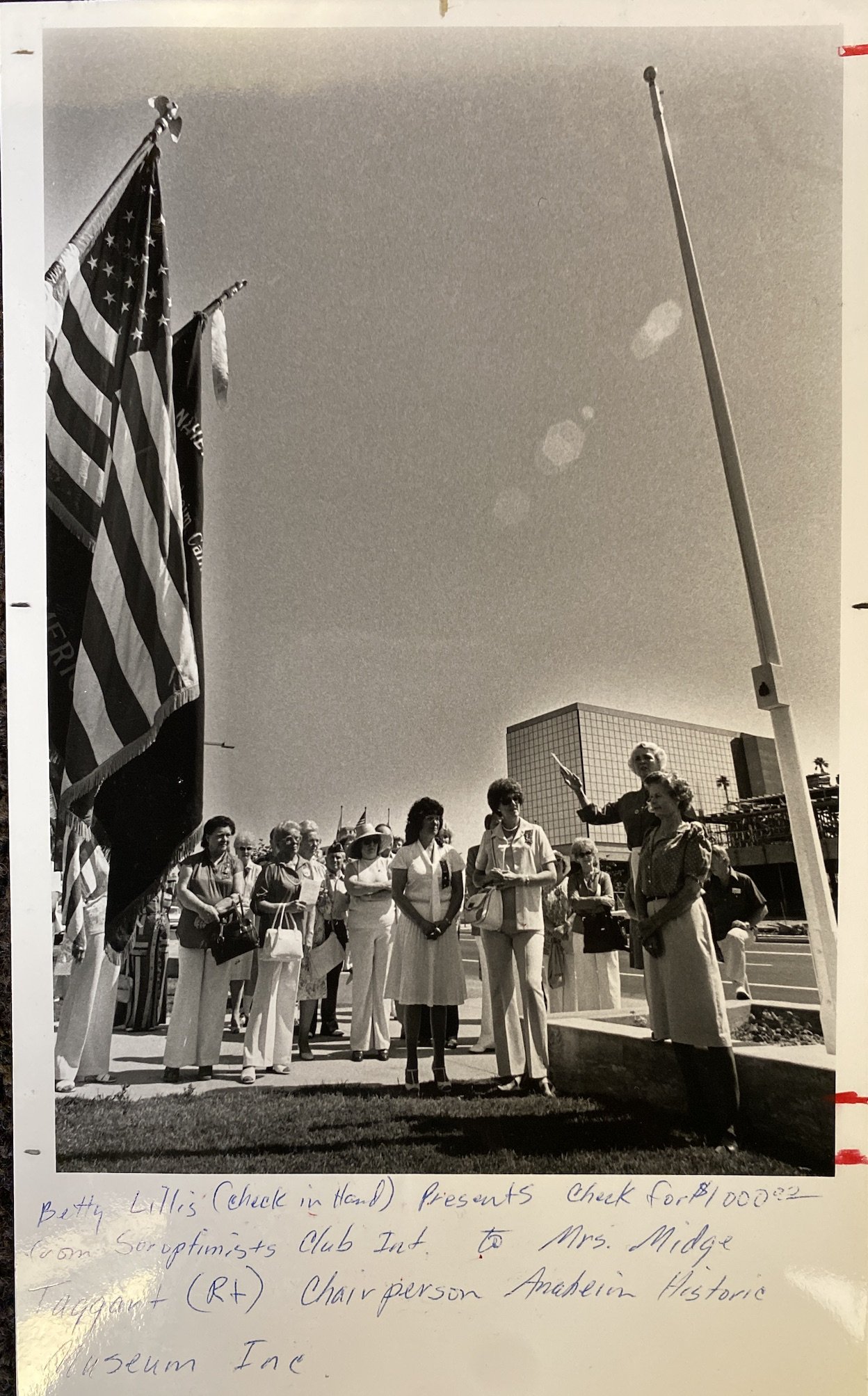

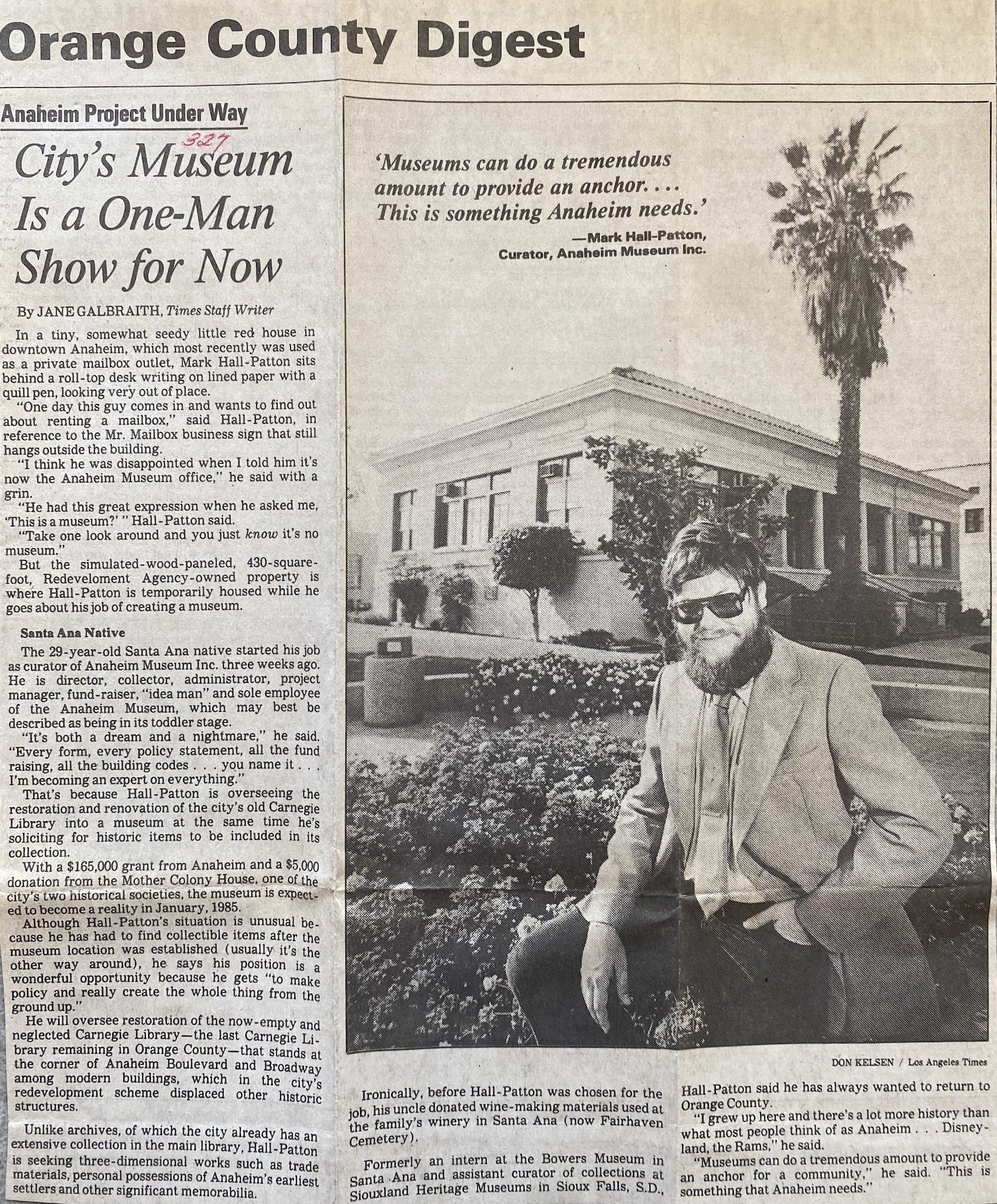

In early 1984, Mark Hall-Patton was hired as the Anaheim Museum’s first employee.[18] Hall-Patton, who retired in 2021 as the head of Clark County Museums in Nevada, and is known for his regular appearances on the History Channel show, “Pawn Stars,” grew up in Santa Ana and received his BA from the University of California Irvine.[19] As the first director of the new museum, Hall-Patton finalized the lease agreement with the City, oversaw early restoration projects, and launched membership promotion and fundraising. He recalls the largest donation at the time of $45,000.00 from Carl’s Jr. founder and Anaheim resident, Carl Karcher and his wife, Margaret Karcher. Before Hall-Patton left for an opportunity in San Luis Obispo in 1985, the museum staged its first exhibit and he and the museum board had raised over $300,000.00.[20]

Mildred “Midge” Taggart

The historic record points to many people involved in saving the Anaheim Carnegie Library building but Midge Taggart stands out as keeping the flame burning from early on, through the ups and downs. Beginning in 1977, Taggart led the Community Steering Committee that culminated in the creation of the non-profit, Anaheim Museum Inc. of which she was President and Co-chair until 1984. She was instrumental in the museum’s earliest acquisitions and fundraising initiatives. Mark Hall-Patton said Taggart was the steady presence who recruited the right people for the board and although she wasn’t political, was persistent and always focused on bringing the museum to fruition. She also rolled up her sleeves. At the time, Hall-Patton recalled, buildings were being razed all around the future museum, and developers offered salvaged items. Hall-Patton said Taggart regularly picked up and stored antiques and memorabilia in her home before the museum was ready to receive them.

Mildred May Loudon Taggart (1913-1994) was ten when she and her family moved from Santa Ana to Anaheim. She graduated from Anaheim High School in 1933, then Santa Ana Junior College, and worked as a graphic artist for her family’s newspaper.[21] The Loudons were prominent in civic affairs in Anaheim and the County.(22) Hazel and Lotus Loudon co-founded the Anaheim Bulletin (later, the Bulletin) in 1923.(23) Midge Loudon married Donald Taggart in 1938 and after a period living elsewhere, she resided in Anaheim until her death in 1994.

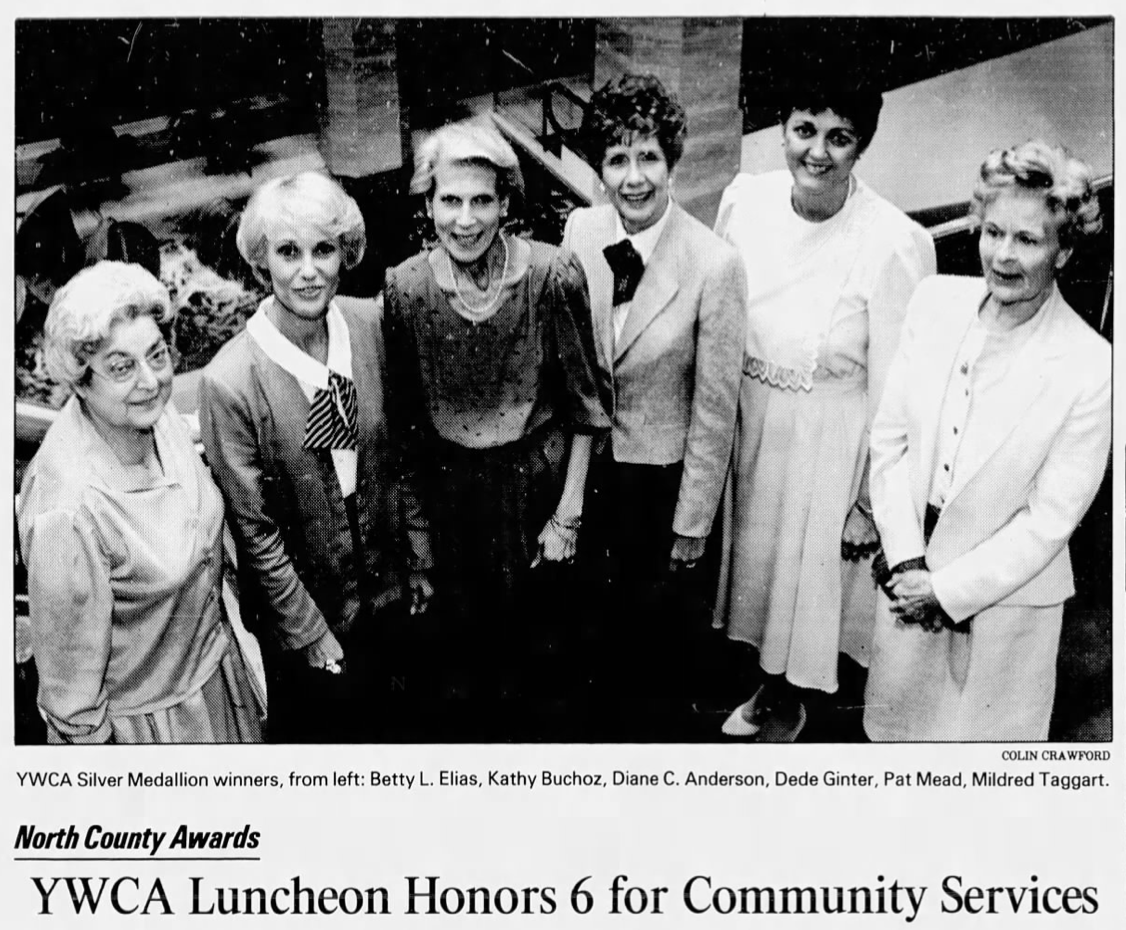

For much of her adult life, Taggart was an active volunteer for the symphony group that became the Pacific Symphony. She was active in the Women’s Division of the Anaheim Chamber of Commerce including as Chair of the Chamber’s Civic Improvement Committee.(24) In 1982, the Chamber recognized Taggart for her community service and in 1985 she was recognized by the YWCA with seven other women in the county for outstanding contribution to her community. (25) The article announcing the 1982 local award reveals Taggart’s involvement in other historic preservation initiatives in Anaheim. It said:

Taggart, recognized for her contributions in helping preserve historical buildings in the city, is a member of the Red Cross and has acted as liaison between the Anaheim Redevelopment Commission and the Red Cross to acquire furnishings for the old Victorian Red Cross house. She was also one of the original 12 members of the Anaheim Historical Society, founded five years ago.(26)

Since 1985 when the Anaheim Museum officially opened to the public, the old Carnegie library has provided a locus for the history of Anaheim. Today, the library building is part of a complex called Muzeo Museum and Cultural Center, which includes the history room of the Anaheim Public Library called the Anaheim Heritage Center. Artifacts collected since Midge Taggart’s time are on display within the Carnegie building in an exhibit, “Walk Through Local History,” which you can see virtually here: Muzeo’s Anaheim Local History Virtual Tour. Established in 2007, Muzeo’s mission is still routed in local history but it has a broader focus on the diverse cultural heritage of Anaheim and the region.

BY Krista Nicholds

ENDNOTES

[1] Headline of Santa Ana Register, Article, Folder, Anaheim Library Services Division, Anaheim Heritage Center (AHC Collection).

[2] Letter dated February 6, 1907 addressed to Edward Merritt, City Clerk, Anaheim, Cal, signed by Andrew Carnegie’s private secretary J. Bertram. AHC Collection.

[3] Konig land sale

[4] City trustees approve 10% maintenance

[5] Theodora Jone, Carnegie Libraries Across America: A Public Legacy, New York: John Wiley and Sons and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1997, 35.

[7] John Austin of Austin, Field and Fry competed for the library commission against Homer W. Glidden, Reeves, Baillie & Co., Edward C. Kent, Octave Lagman, Kelley & Newberry. Anaheim Gazette, December 19, 1907. The Upland library designed by Homer Glidden is on the National Register of Historic Places and is a community center today.

[8] Sources include the Los Angeles Conservancy website; Finding Aid for the John C. Austin Papers, Online Archive of California; and the Pacific Coast Architecture Database.

[9] Letter dated August 12, 1907, from Edward B. Merritt, City Clerk for the City of Anaheim Board of Trustees to Andrew Carnegie, AHC Collection.

[10] No budget for books or furniture. FN for Kuechel and Rowley, Orange contractors.

[11] “City’s Public Library True Servant of People,” Anaheim Bulletin, December 1928, collection of Anaheim History Center; and “Librarian Retires After 38 Years Of Service Here,” Anaheim Gazette, Thursday, October 8, 1953, AHC Collection.

[12] “Librarian Retires After 38 Years Of Service Here,” Anaheim Gazette, October 8, 1953,

[13] Stephen J. Faessel, “Our Carnegie Library’s 90th Birthday,” 1998. AHC Collection.

[14] “City Council Acts to Save Old Library,” The Register, November 21, 1974; and “Anaheim Moves to Preserve Old Carnegie Library,” Los Angeles Times, November 25, 1974. From Anaheim History Center folder, “ Anaheim. Library Services Division- Carnegie Library Building, 1907.“

[15] Resolution 78R-138, Feb 28, 1978. See Faessel essay, 1998.)

[16] Money was allocated for a number of engineering and architecture studies beginning in 1978 with $50,000 from the Redevelopment agency. Structural engineer Robert Lawson of Bissell-August Associates was hired to do the engineering survey in 1978. In 1983, $40,000 was allocated by City Council for restoration plans to be developed by Thirtieth Street Architects of Newport Beach. The Register, October 11, 1983.

[17] “Former City Library to House Relics,” The Register, September 11, 1980.

[18] Jane Galbraith, “City’s Museum Is a One-Man Show for Now,” Los Angeles Times, March 26, 1984.

[19] Mark Hall-Patton, interview by phone with author, June 24, 2021.

[20] “Pledges Helping Museum,” Anaheim Hills Journal, August 30, 1984. AHC Collection.

[21] “Anaheim Bridal Rites are of County Wide Interest,” Santa Ana Daily Register, January 10, 1938, 10.

(22) “Death Claims L.H. Loudon at Anaheim,” Los Angeles Times, May 1, 1951.

(23) “Hazel Loudon Rites Slated,” Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1974.

(24) “Magnolia Ceremony Planned by Anaheim,” Los Angeles Times, March 27, 1969.

(25) “YWCA Luncheon Honors 6 for Community Services,” Los Angeles Times, April 3, 1985.

(26) “Five Anaheim Women Receive Awards,” Los Angeles Times, March 2, 1982.