Linda Shay is Educating Brea and the U.S. About the Mills Act, Historic Preservation, and Redlining

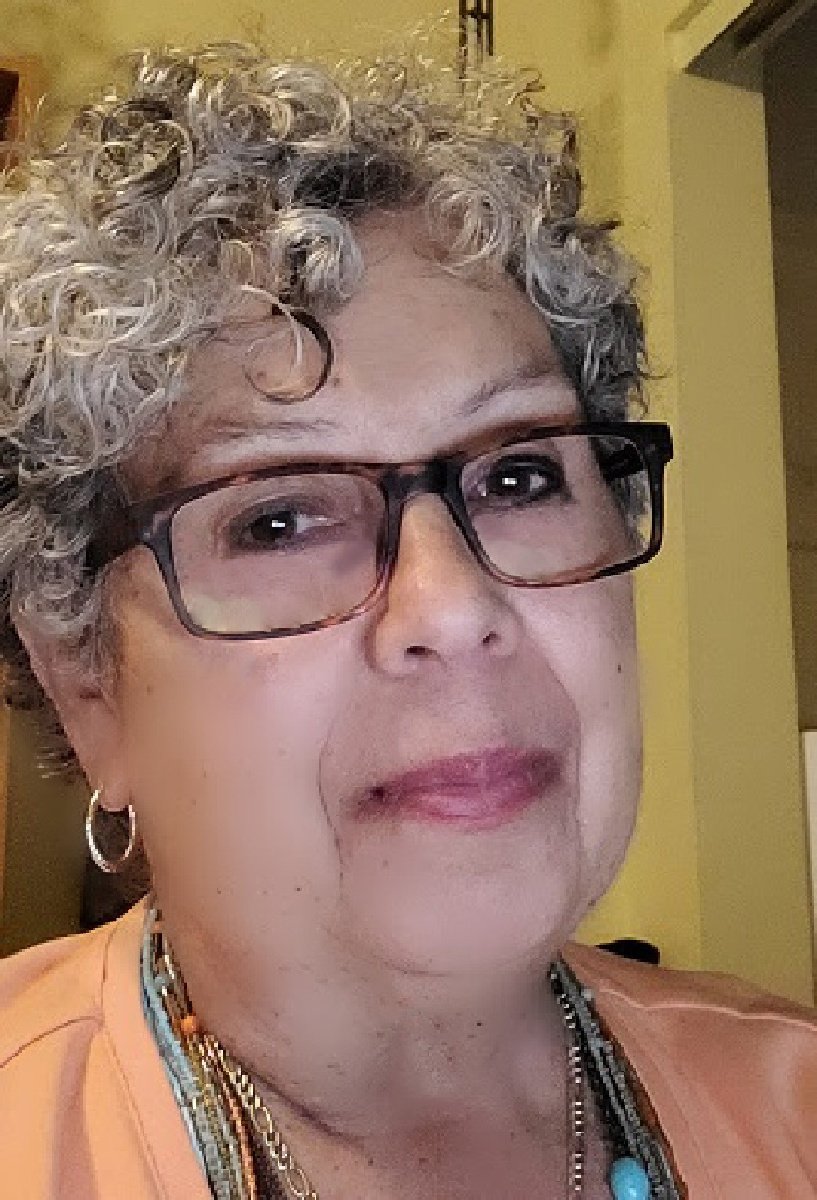

Yes, Brea has an extensive public art collection, spawned some major league baseball players, and won the 2001 California Redevelopment Association's Award of Excellence in Community Revitalization for turning its old downtown into a mixed-use town center. But an intriguing history lurks in those canyons and hills. The person researching the city’s past is Linda Leach Shay, Ph.D., Executive Director and Curator of the Brea Museum & Historical Society. She’s also an adjunct professor at the University of Maryland.

One of Brea’s architectural gems that’s remarkably preserved is the original Brea City Hall, an Art Deco and Spanish Colonial Revival, 1928-built beauty designed by architect Allen Ruott. The Los Angeles architect also designed the adjacent park, bathhouse, and swimming pool–all of which are on the National Register of Historic Places. The city also has 18 homes that are Mills Act contract properties. All but one were completed during redevelopment in the 1990s. The other was in 2016. Recently, another home was designated to the Historic Registry.

“We’re hopeful the homeowners will go forward with their application for the Mills Act,” says Shay. Owners of historic buildings may qualify for property tax relief if they pledge to rehabilitate and maintain the historical and architectural character of their properties for at least a 10-year period, according to the California State Office of Historic Preservation.

In addition to working with the City to include the Brea Historical Society on its website as a resource, Shay has revised documentation and is educating the public about the program. While the city is committed to reviving its historic preservation program, other projects take higher priority, says Shay. “I just keep ‘poking the bear’.” (For information about the City of Brea Historic Preservation program, visit https://www.ci.brea.ca.us/1657/Historic-Preservation

Shay hopes more eligible homeowners will be interested through awareness. She believes the major obstacle is the cost to apply for historical designation, which is just over $1,500. Of course, getting that historical designation is required before one can apply for the Mills Act. “We’re trying to reduce those costs somehow,” says Shay.

Originally from Long Island, New York, Shay has a B.A. in history and a Ph.D. in education. Her focus has been on the 20th century, specifically how propaganda informs social experience and historical memory. Relocating to California in 1984, Shay lived in Anaheim before buying a home in Brea in 1996. Her work with the historical society started in 2015, when the society was going through a “rough patch”, had no director, and was considering closing the museum.

While Brea’s oil and citrus industries are a familiar part of the city’s history, few residents know that Brea was a redlining city: one of many across the country that practiced residential segregation. This housing system separated Americans by race, ethnicity, and class, giving white Americans advantages that were unavailable to others. The system created racial disparities that still exist.

The Brea Historical Society is one of six institutions that are part of a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) studying de-facto segregation in the United States. The project is called Unvarnished: Housing Discrimination in the Northern and Western United States. In addition to the BHS, participating organizations include the Noah Webster House in Connecticut, Oak Park Foundation in Illinois, the Ohio History Connection, and The Castle in Wisconsin.

“Our findings confirm that Brea was always a white community and advertising efforts in the mid-20th century sought to keep it that way,” says Shay. “I encourage everyone to visit the website and view the online exhibit.”

The website is https://www.unvarnishedhistory.org/. For more information about the Brea Museum and Historical Society, visit https://breamuseum.org/

By Lisa Taylor